Issue Summary

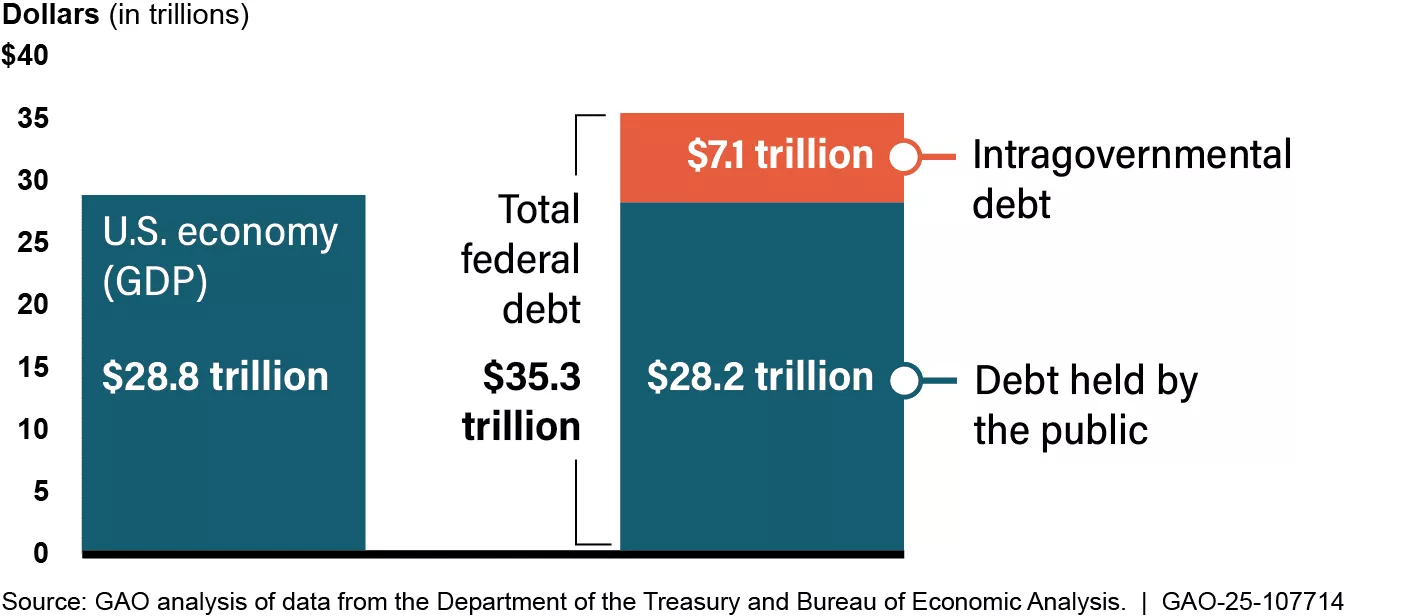

By the end of FY 2023, total federal debt was $33.1 trillion. 79% was debt owed to investors (debt held by the public) and 21% was debt the government owed itself (what Treasury owes to other parts of the government).

Image

To meet government borrowing needs, Treasury borrows money from the public by issuing Treasury securities (e.g., bills, notes, bonds, etc.) to investors on a regular and predictable schedule. Strong investor demand for Treasury securities helps maintain low government borrowing costs. Treasury must continue to promote strong demand for its securities among different types of investors while making debt issuance decisions—such as what type of Treasury security to issue and in what quantity—that navigate financial and economic conditions.

Some of Treasury’s considerations include:

- Uncertain borrowing needs. Policy changes and economic conditions can quickly affect federal cash flow. For example, the federal response to COVID-19 led to unprecedented spending. Treasury quickly sold securities to raise $3.8 trillion. Meanwhile, Treasury increased its cash-on-hand to over $1 trillion to help deal with the uncertainty around federal pandemic-related spending. Other external events like recessions, military conflicts, and emergencies (e.g., natural disasters such as hurricanes) can also dramatically affect borrowing needs.

- Uncertainty about future interest rates. Treasury’s debt management goal is to borrow at the lowest cost over time, while also managing its debt portfolio to mitigate rollover risk (the risk that it may have to refinance its debt at higher interest rates). To do this, Treasury needs to consider the mix of longer-term and shorter-term securities that it offers. Longer-term securities typically have higher interest rates than short-term securities but offer more certainty for budget planning because they do not mature as frequently. On the other hand, short-term securities usually have lower interest rates but must be refinanced more frequently, potentially at higher interest rates.

- Debt limit uncertainty. The debt limit is a legal limit on the total amount of federal debt that can be outstanding at one time. Delays in suspending or raising the debt limit create debt and cash management challenges for the Treasury. Delays in raising the debt limit have occurred in 12 of the last 13 fiscal years. As a result, Treasury has often used extraordinary actions, such as suspending investments or temporarily disinvesting securities held in federal employee retirement funds, to remain under the limit. Once it has exhausted all extraordinary actions, Treasury may not issue debt without further action from Congress and the President. If Treasury does not have enough cash on hand to meet its financial commitments, Treasury could be forced to delay payments until sufficient funds become available. Treasury might eventually be forced to default on legal debt obligations, which would have devastating effects on U.S. and global economies. However, there are alternative approaches to the debt limit that would mitigate these risks.

- Changing financial markets. Disruptions in the Treasury market could reduce investor demand for Treasury securities and negatively affect Treasury’s ability to borrow money at low cost. For example, the shock of COVID-19 to financial markets led many investors to cash in their Treasury securities at the same time, which caused higher interest rates on some securities and strained market trading. Other market disruptions in recent years have also led to periods of stress. Continued market disruptions pose risks to the liquidity and efficiency of the Treasury market, at a time when debt issuance and debt held by the public continues to grow.

Image