Issue Summary

The federal government is responsible for conducting a number of activities to protect U.S. borders and enforce immigration laws, mainly through the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Justice (DOJ). However, there are a number of areas in which these agencies can improve how they manage and implement these activities—on which they spend billions of dollars each year.

For instance:

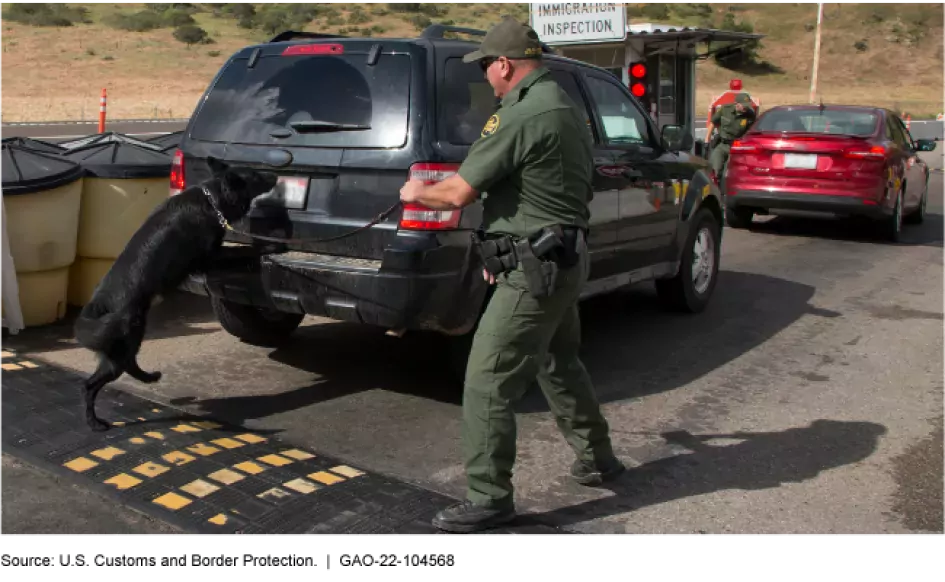

- Checkpoint data. DHS’s U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is responsible for securing U.S. borders at and between ports of entry. Within CBP, U.S. Border Patrol operates over 100 immigration checkpoints along U.S. borders where agents screen vehicles to identify noncitizens who are potentially removable; they may also enforce U.S. criminal law. Agents are required to collect data on checkpoint activity, including how many smuggled people are apprehended and how many drug seizures were made using canines. However, agents at checkpoints inconsistently documented this data, which makes oversight of these checkpoints difficult.

Border Patrol Checkpoint Canine Team Inspects a Vehicle

Image

- Incidents involving CBP personnel. CBP personnel may be involved in “critical” incidents that result in serious injury or death, such as a child dying in custody. They may also be involved in less serious, “noncritical” incidents, such as a vehicle accident that results in property damage. While CBP’s Office of Responsibility is to investigate critical incidents, Border Patrol sectors respond to noncritical incidents involving their agents and assess the agency’s liability for associated property damage. However, without guidance or oversight from headquarters, the sectors approach noncritical incident response inconsistently and there are concerns their activities may infringe on investigations of critical incidents.

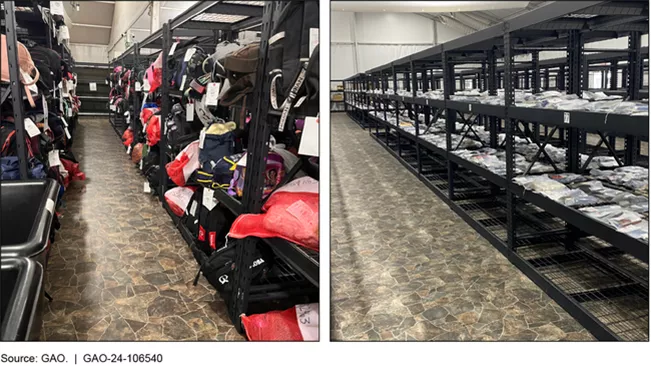

- Noncitizens' personal property. CBP may hold noncitizens in short-term custody in facilities along the southwest border. CBP is to collect their personal property, store it, and return it when they are released. CBP has guidance for handling personal property, but some of it is unclear— resulting in field locations interpreting it differently. For example, some locations discard property over a certain amount or size, while others don’t. Also, field locations' instructions for people to retrieve their personal property after release are inconsistent, and CBP doesn’t monitor how locations implement its guidance.

Property Storage Rooms at Two CBP Facilities

Image

- Immigration enforcement. DHS’s U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is responsible for immigration enforcement within the U.S. This includes making arrests, providing safe confinement of noncitizens in detention facilities, and removing noncitizens. Regarding detentions, ICE’s public reporting doesn’t include all people it detains in its facilities, resulting in underestimates of tens of thousands of people. For example, in FY 2022, ICE’s reporting excluded detentions of 136,706 individuals. ICE also doesn’t fully explain its methodology. As a result, Congress and the public may not have a complete understanding about how to interpret the data.

- Immigration detention. DHS and ICE use various inspection programs to help ensure detention facilities for noncitizens are safe, secure, and humane. However, some of these programs don’t have clear performance goals and measures. This makes it hard to assess how effective the programs are at ensuring facilities meet standards for immigration detention.

- Alternatives to Detention. ICE is also responsible for monitoring noncitizens it releases into the community during their immigration court proceedings and has increasingly used its Alternatives to Detention program to do so. The program offers ICE options for monitoring people (e.g., GPS or home visits) to help ensure compliance with release requirements, such as appearing in court. ICE uses a $2.2 billion contract to administer this program, but it doesn't fully assess how the program is working or ensure that the contractor meets standards.

- Immigration fraud. DHS’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) processes millions of applications and petitions for immigration benefits each year. USCIS also investigates potential immigration fraud. For example, USCIS investigates concerns that some marriages are formed to evade U.S. immigration law or illegally obtain immigration benefits, such as permanent residence. USCIS uses a staffing model to estimate how many immigration officers it needs for its antifraud workload. However, the model doesn't adequately reflect operating conditions. USCIS has also made a variety of changes to its antifraud activities, but it hasn’t evaluated their effectiveness or efficiency.

- Immigration reviews. The Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) holds immigration hearings to determine whether noncitizens will be removed from the country. As of July 2024, EOIR had a backlog of about 3.5 million pending cases. Noncitizens are expected to attend their hearings, and failing to show up could result in removal from the U.S.—unless a judge waives their appearance. But EOIR only started collecting data on hearing appearances and waivers in December 2024. Publicly reporting this data could help inform Congress’s oversight of immigration court activities.

Recent Reports

GAO Contacts

Rebecca S. Gambler

Chief Quality Officer and Managing Director of Audit Policy and Quality Assurance

Audit Policy and Quality Assurance