U.S. Department of Health and Human Services--Application of Anti-Lobbying and Publicity or Propaganda Provisions

Highlights

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) did not violate certain legal provisions when it used its appropriations for activities related to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), including the reduction of certain planned public outreach, changes to the information on the HHS.gov and HealthCare.gov websites, agency postings on official HHS Twitter accounts, and the production and dissemination of videos through the official HHS YouTube account. First, HHS acted within its permissible range of discretion when it reduced certain planned public outreach because the curtailment of this outreach did not result in a program that was inconsistent with the requirements of applicable law. Second, HHS did not violate the publicity or propaganda or anti-lobbying provisions contained in appropriations acts, or an anti-lobbying provision contained in PPACA, through its agency communications with the public. HHS's appropriations are generally available for communicating with the public about HHS's activities and the policy views that underlie those activities, and the communications here were not self-aggrandizing, purely partisan, or covert. In addition, HHS did not make a clear appeal to the public to contact Members of Congress about pending legislation, nor did it adopt any third party's appeal. Further, HHS did not violate a provision restricting lobbying by grant or contract recipients because that provision does not apply to situations where the activity is directed by the agency and the activity is merely supported by a contractor. Lastly, HHS's changes to its HealthCare.gov website, which bore no apparent relation to legislative or regulatory modifications, did not violate the PPACA provision prohibiting the use of certain Exchange funds for lobbying activities.

B-329199

September 25, 2018

Congressional Requesters

Subject: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services—Application of Anti‑Lobbying and Publicity or Propaganda Provisions

This responds to your request for our opinion regarding whether certain U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) activities concerning the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) were consistent with appropriations laws.[1] The activities at issue are the reduction of certain planned public outreach, changes to the information on the HHS.gov and HealthCare.gov Web sites, agency postings on official HHS Twitter accounts, and the production and dissemination of videos through the official HHS YouTube account. You asked whether these activities were consistent with (1) the purpose statute, 31 U.S.C. § 1301(a), which provides that appropriations may be used only for the purposes for which they were appropriated; (2) section 718 of the Financial Services and General Government Appropriations Act, 2017, which prohibited the use of HHS appropriations for unauthorized publicity or propaganda purposes; (3) section 715 of the Financial Services and General Government Appropriations Act, 2017, which prohibited the use of HHS appropriations for indirect or grassroots lobbying in support of, or in opposition to, pending legislation; (4) section 503 of the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2017, which prohibited the use of HHS appropriations for indirect or grassroots lobbying in support of, or in opposition to, pending legislation and placed restrictions on the use of HHS’s appropriations for the salaries or expenses of grant or contract recipients; and (5) section 1311 of PPACA, which prohibits the use of funds intended for the administrative or operational expenses of an American Health Benefit Exchange (Exchange) for lobbying for certain measures.

In accordance with our regular practice, we contacted HHS to seek factual information and its legal views on this matter.GAO, Procedures and Practices for Legal Decisions and Opinions, GAO-06-1064SP (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2006), available at www.gao.gov/products/GAO-06-1064SP; Letter from Managing Associate General Counsel, GAO, to Acting General Counsel, HHS (Aug. 14, 2017). In response, HHS provided its explanation of the pertinent facts and its legal analysis. Letter from General Counsel, HHS, to Managing Associate General Counsel, GAO (Jan. 22, 2018) (Response Letter).

As explained below, we conclude that HHS did not violate the described provisions through the activities in question. Our opinion applies the legal provisions to the facts before us and draws no conclusions regarding the merits of the health care legislation at issue or the wisdom of HHS’s actions.

BACKGROUND

By executive order, the President declared his Administration’s policy “to seek the prompt repeal of [PPACA].” Exec. Order No. 13765, Minimizing the Economic Burden of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Pending Repeal, 82 Fed. Reg. 8351 (Jan. 20, 2017). The order required the HHS Secretary and the heads of all other executive departments and agencies with responsibilities under PPACA to exercise their authority and discretion, in accordance with the law, to minimize perceived economic burdens under PPACA and to allow states more flexibility and control to implement health care programs and create a free and open market. Id. HHS subsequently: (1) reduced certain planned outreach activities; (2) made changes to information on HHS.gov and HealthCare.gov; (3) shared information regarding health care reform using official agency Twitter accounts; and, (4) produced and disseminated videos regarding PPACA on the official HHS YouTube account. We discuss each of these activities in turn.

Reduction of PPACA‑related outreach

Section 1103 of PPACA requires the HHS Secretary to establish a Web site through which individuals and small businesses may obtain information on coverage options, using a standardized format to present such information. Pub. L. No. 111‑148, title I, subtitle B, § 1103, 124 Stat. 119, 146 (Mar. 23, 2010), classified at 42 U.S.C. § 18003; id., title X, subtitle A, § 10102(b), 124 Stat. at 892, classified at 42 U.S.C. § 18003. This Web site, HealthCare.gov, is also the interface for the federal marketplace through which consumers may select and enroll in health care plans.[2] HHS, What is the Health Insurance Marketplace, available at www.hhs.gov/answers/affordable-care-act/what-is-the-health-insurance-marketplace (last visited Sept. 24, 2018). For the 2017 benefit year, the annual open enrollment period for individuals to sign up for a qualified health plan began on November 1, 2016, and extended through January 31, 2017. 45 C.F.R. § 155.410. During the final days of the open enrollment period, HHS officials partially terminated two contracts for “PPACA-related outreach services” pursuant to a “policy determination to reduce agency spending.” Response Letter, at 7. This action resulted in termination costs to the government of at least $1.1 million and potential savings of approximately $5.2 million. See HHS Inspector General, Review of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Cancellation of Marketplace Enrollment Outreach Efforts, Report No. OEI‑12‑17‑00290 (Oct. 25, 2017) (OIG Report).

Changes to HHS.gov and HealthCare.gov

HHS made changes to the presentation of information regarding PPACA on its HHS.gov and HealthCare.gov Web sites.[3] For example, an HHS.gov Web page on “providing relief” for patients states that PPACA has “done damage” and “created great burdens for many Americans.” HHS, Providing Relief Right Now for Patients, available at www.hhs.gov/healthcare/empowering-patients/providing-relief-right-now-for-patients (last visited Sept. 13, 2018). The page provides links to information on various department activities, including an update encouraging the use of private‑sector insurance broker Web sites rather than the “complicated and time‑consuming” HealthCare.gov. HHS, Making Online Insurance Enrollment Easier for You, available at www.hhs.gov/healthcare/empowering-patients/providing-relief-right-now-for-patients/making-online-insurance-enrollment-easier-for-you (last visited Sept. 13, 2018). As another example, HHS made changes to the presentation of information regarding costs and savings on HealthCare.gov. HHS officials explained that these types of changes have been made on prior occasions and described the changes as reflective of the messaging priorities at a given time. Response Letter, at 7. HHS further explained that it modifies the content of the HealthCare.gov Web site depending on the status of open enrollment. Id.

HHS obligated the Service and Supply Fund for expenses associated with the operation of HHS.gov. Response Letter, at 8. It also obligated amounts from the FY 2016 Office of the Secretary, General Departmental Management appropriation for this purpose. Id. HHS obligated its Exchange[4] user fee collections for expenses associated with the operation of HealthCare.gov. Id.

HHS tweets regarding health care legislation

On March 20, 2017, the American Health Care Act of 2017 (AHCA), H.R. 1628, was introduced in the House of Representatives. H.R. 1628, 115th Cong. (2017). The House passed an amended version of the bill on May 4, 2017. Id. The bill was received in the Senate on June 7, 2017, and placed on the Senate Legislative Calendar under General Orders on June 8, 2017. Id. The Senate considered a series of amendments, and the bill was ultimately returned to the calendar on July 28, 2017. Id.

As Congress considered the health care legislation, the HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs (ASPA) used two of HHS’s official Twitter accounts, @HHSMedia[5] and @HHSGov,[6] to post several tweets concerning AHCA and PPACA. For example, @HHSMedia:

- Retweeted a March 24 tweet by Fox & Friends: “@SecPriceMD urges the House to pass American Health Care Act.” The message included a photo from then‑Secretary Price’s appearance on Fox News with the caption, “Take it or leave it, Potus: Pass the bill today or O’care stays!” See @foxandfriends, Twitter (Mar. 24, 2017, 08:30 AM), available at https://twitter.com/foxandfriends/status/845251358265528321.

- Retweeted then-Secretary Tom Price’s message, initially tweeted on May 5: “Great to join @foxandfriends this morning to talk about next steps for #AHCA. Engagement is key as this process moves forward.” The message included a video clip of Price discussing AHCA on Fox News, as shared by the Fox & Friends Twitter account. See @SecPriceMD, Twitter (May 5, 2017, 11:11 AM), available at https://twitter.com/SecPriceMD/status/860512231099957249.

- Retweeted Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Administrator Seema Verma’s (@SeemaCMS) message, initially tweeted on May 22: “#AHCA is going to increase choice, lower premiums and put patients first. Joined @TeamCavuto @FoxBusiness today to discuss.” See @SeemaCMS, Twitter (May 22, 2017, 01:56 PM), available at https://twitter.com/SeemaCMS/status/866714280011366402.

- Shared an HHS report on individual market premium changes, along with the statement, “New #HHSReport sobering reminder of #Obamacare fail & need for #AHCA.” See @SpoxHHS, Twitter (May 23, 2017, 09:17 AM), available at https://twitter.com/SpoxHHS/status/867187802659844097.

The @HHSGov Twitter account also expressed support for PPACA repeal. The @HHSGov account retweeted then‑Secretary Price’s June 5 message: “We will continue to work to create a #healthcare system that is truly responsive to the needs of #patients & #smallbiz. #RepealAndReplace.” See @SecPriceMD, Twitter (June 5, 2017, 06:21 PM), available at https://twitter.com/SecPriceMD/status/871854551808307202. This tweet contained four “hashtags”: “#healthcare,” “#patients,” “#smallbiz,” and “#RepealAndReplace.” A hashtag on social media consists of the “#” symbol followed by a word or phrase, using no spaces. See How to Use Hashtags, available at https://help.twitter.com/en/using-twitter/how-to-use-hashtags (last visited Sept. 14, 2018). A hashtag is used to index messages that contain the same hashtag, allowing users to view other tweets with that hashtag. Id. Very popular hashtags may become “trending topics,” potentially increasing their visibility. Id. The “RepealAndReplace” moniker has been used by other social media users advocating for changes to health care legislation, including the America’s Liberty Committee, a self-described grassroots lobbying organization. On May 3, the America’s Liberty Committee, @americasliberty, posted the message: “Call Congress at 202-224-3121 and demand full repeal of ObamaCare #FullRepeal #RepealAndReplace #KeepYourPromise #StandWithRand.” @americasliberty, Twitter (May 3, 2017, 08:25 AM), available at https://twitter.com/americasliberty/status/859745762997149697. Clicking on a hashtag directs users to other messages containing the hashtag. Readers of the @HHSGov message clicking on the #RepealAndReplace could have potentially reached the America’s Liberty Committee lobbying tweet.

HHS production and dissemination of videos

Through its @HHSGov Twitter account, HHS shared several video clips, initially posted by then‑Secretary Price, of small business owners commenting on PPACA’s impact. Response Letter, at 4. HHS featured longer versions of these and other, similar video statements—a total of 23 videos—on its YouTube channel. HHS categorized these videos under the headings, “Families Burdened by Obamacare,” “Doctors and Healthcare Professionals Burdened by Obamacare,” and “Women Small Biz Owners Burdened by Obamacare.” HHS, Families Burdened by Obamacare, available at www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrl7E8KABz1EifD5BWCrauFUNqrMEKAQ0 (last visited Sept. 14, 2018); HHS, Doctors and Healthcare Professionals Burdened by Obamacare, available at www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrl7E8KABz1F8RH8FqQ67zNYtgKz2zV2r (last visited Sept. 14, 2018); HHS, Women Small Biz Owners Burdened by Obamacare, available at www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrl7E8KABz1G9hBuZb9nB4VggqAvrfvAC (last visited Sept. 14, 2018). The videos under the headings “Families Burdened by Obamacare” and “Doctors and Healthcare Professionals Burdened by Obamacare” each displayed an HHS logo in the corner of the screen. The videos under the heading “Women Small Biz Owners Burdened by Obamacare” did not contain this emblem or otherwise identify the agency within the video. Clips from this collection of videos were among those shared via @HHSGov’s retweets of then‑Secretary Price.

According to HHS, the individuals featured in the videos attended roundtable discussions at the White House regarding the impact of PPACA. Response Letter, at 4. Prior to the roundtable discussions, HHS’s Office of Intergovernmental and External Affairs contacted the participants and informed them of the opportunity to share their stories on video. Id. On the date of each roundtable discussion, ASPA then contacted the individuals who had elected to record a video, and these individuals traveled from the White House to HHS’s television studio. Id. At the studio, ASPA’s Broadcast Communications Division videotaped their statements. Id.

HHS obligated its FY 2017 Office of the Secretary, General Departmental Management appropriation for the salaries of the employees responsible for creating the described videos, as well as for invitational travel expenses for certain video participants. Id. To provide day‑to‑day and surge support services for the television studio, HHS awarded a task order under its overarching single‑award, indefinite‑delivery, indefinite‑quantity (IDIQ) contract for television studio support services. Response Letter, at 4. See Order No. HHSP23337003T, Feb. 8, 2017; HHS Contract No. HHSP233201600009I, Jan. 29, 2016.

According to HHS, operation of the agency’s television studio is a common administrative service it provides to all HHS agencies and offices. Response Letter, at 4. As such, HHS informed us that it obligated the Service and Supply Fund to award the task order and then reimbursed the Service and Supply Fund pursuant to its account adjustment authority.[7] Response Letter, at 4; E‑Mail from Associate Deputy Assistant Secretary, Office of Budget, HHS, to Managing Associate General Counsel, GAO, Subject: Charging of studio costs (Sept. 4, 2018) (citing 31 U.S.C. § 1534) (Studio Costs E‑Mail). In that regard, HHS states that the reimbursement for the costs related to the YouTube videos at issue here “was not charged to an appropriation that includes user fees.” Studio Costs E‑Mail. Further, HHS “represents that the cost of producing the videos under discussion was effectively paid by annual [Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services] Program Management funds . . . which were available to fund the videos under discussion.” Id.

DISCUSSION

At issue here is whether HHS’s activities concerning PPACA were consistent with (1) the purpose statute, 31 U.S.C. § 1301(a), which provides that appropriations may be used only for the purpose for which they were appropriated; (2) section 718 of the Financial Services and General Government Appropriations Act, 2017, which prohibited the use of HHS appropriations for unauthorized publicity or propaganda purposes; (3) section 715 of the Financial Services and General Government Appropriations Act, 2017, which prohibited the use of HHS appropriations for indirect or grassroots lobbying in support of or in opposition to pending legislation; (4) section 503 of the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2017, which prohibited the use of HHS appropriations for indirect or grassroots lobbying in support of, or in opposition to, pending legislation and limited the use of HHS’s appropriations for the salaries or expenses of grant or contract recipients; and (5) section 1311(d)(5)(B) of PPACA, which provides that fees collected pursuant to section 1311 are not available for “promotion of Federal or State legislative and regulatory modifications.” We will consider these statutory provisions in two different factual contexts: first, the reduction of certain planned public outreach; and second, communications from HHS to the public.

Reduction of PPACA‑related outreach

Following the President’s January 20, 2017 executive order “to seek the prompt repeal of [PPACA],” HHS officials partially terminated two contracts for “PPACA‑related outreach services” during the final days of the open enrollment period for the 2017 benefit year, which ended on January 31, 2017. Exec. Order No. 13765; Response Letter, at 7. According to HHS, the partial terminations were a result of a policy determination to reduce agency spending and were carried out in accordance with the terms and conditions of the contracts. Response Letter, at 7. This action resulted in termination costs to the government of at least $1.1 million and potential savings of approximately $5.2 million. OIG Report, at 5. HHS maintains that it directed certain paid advertising and low-cost activities to continue, and HHS officials stated that the department “continues to undertake activities to inform the public about PPACA and open enrollment.” Response Letter, at 7. See OIG Report, at 4. The issue here is whether HHS’s appropriations were available for costs to reduce certain planned PPACA‑related outreach activities.

Under the purpose statute, appropriations “shall be applied only to the objects for which the appropriations were made.” 31 U.S.C § 1301(a). Before an agency may obligate or expend funds for any purpose, it must first determine that it has an appropriation that is available for that particular purpose. See B‑329373, July 26, 2018. The authorized purposes of an appropriation depend on the relevant statutory language. An expenditure that is not expressly provided for in statute must bear a reasonable and logical relationship to the purpose for which the funds were appropriated. Id.

When we review the agency’s determination, the question is not whether we would have made the same determination as the agency did. See B‑223608, Dec. 19, 1988. Rather, the question is whether the expenditure falls within the agency’s legitimate range of discretion, or whether its relationship to an authorized purpose or function is so attenuated as to take it beyond that range. Id. See also United States Department of the Navy v. FLRA, 665 F.3d 1339, 1349 (D.C. Cir. 2012).

Whether an agency’s appropriation is available to discontinue activities or to make changes to a program depends on the language of the appropriating and authorizing legislation that govern the program. Expenses pertaining to the termination of activities carried out in furtherance of a statutory program can be paid from funds appropriated for that program, so long as the proposed termination action would not result in such a curtailment of the overall program that it would no longer be consistent with the statutory requirements. 61 Comp. Gen. 482 (1982). For example, the Department of Energy sought to use its Fossil Energy Research and Development appropriation for termination costs and other expenses associated with eliminating activities that were inconsistent with a previous Administration’s view of the proper scope of the Fossil Energy Research and Development Program. Id. Although the authorizing statute required that Energy’s program be designed to advance certain specific categories of energy technology, the particular projects and activities proposed for termination were not explicit requirements of the statute. Id. The statute governing the program afforded considerable discretion to the agency in its implementation, and we did not find the proposed terminations to be an abuse of this discretion. Id.

Contrast this with our opinion regarding the Energy Research and Development Administration’s (ERDA) Clinch River Breeder Reactor Project, in which we concluded that funds appropriated for the project could not be used to implement a proposed curtailment of that project. B‑115398.33, June 23, 1977. Significantly, the proposed reduction in scope would have been inconsistent with the controlling statutory scheme, which authorized ERDA to implement the project in accordance with certain approved criteria. Id. Not only would ERDA’s revised project plan have contravened these criteria, but it would have resulted in a program that did not satisfy the relevant legal requirements. Id.

Here, we consider whether the partial termination of the contracts for “PPACA‑related outreach services” resulted in such a curtailment of the overall program that it is no longer consistent with statutory requirements. As relevant here, PPACA requires that HHS implement the provisions of PPACA and maintain an internet portal. See, e.g., Pub. L. No. 111‑148, title I, subtitle D, part III, § 1321(a), 124 Stat. at 186, classified at 42 U.S.C. § 18041 (requiring that the Secretary issue regulations and establish standards related to Exchanges, the offering of qualified health plans, and other components of Title I of PPACA); Pub. L. No 111‑148, title I, §§ 1103(a), 1311(c)(5), 124 Stat. at 146, 175, classified at 42 U.S.C. §§ 18003, 18031 (requiring that the Secretary establish and maintain an internet portal through which consumers may identify affordable health insurance coverage options).

HHS also conducts certain outreach activities with regard to PPACA. HHS stated that its “PPACA outreach and dissemination activities are, and have been, carried out pursuant to [HHS’s] inherent authority to disseminate information to the public about HHS programs and activities.”[8] Response Letter, at 8. Agencies have general authority to inform the public concerning their programs and policies. See B‑329504, Aug. 22, 2018; B‑319834, Sept. 9, 2010; B‑319075, Apr. 23, 2010; B‑284226.2, Aug. 17, 2000; B‑194776, June 4, 1979. See Response Letter, at 8 (“[T]he HHS Secretary does have authority . . . to disseminate information related to public health and HHS programs, such as programs under PPACA.”) (citing 42 U.S.C. § 300u); id., at 1, 2, 3, 7. Cf. Lincoln v. Vigil, 508 U.S. 182, 193 (1993) (noting that an agency must determine “whether its ‘resources are best spent’ on one program or another” in allocating funds from a lump‑sum appropriation) (citing Heckler v. Chaney, 470 U.S. 821, 831 (1985)); B‑323699, Dec. 5, 2012 (“[A] lump sum appropriation . . . gives an agency the capacity to . . . meet its statutory responsibilities in what it sees as the most effective or desirable way.”).

Here, HHS informed us that, after the partial termination of the contracts at issue, it directed certain paid advertising and low-cost activities to continue. Response Letter, at 7; OIG Report, at 4. Further, HHS officials stated that the department “continues to undertake activities to inform the public about PPACA and open enrollment.” Response Letter, at 7. See OIG Report, at 4. Unlike ERDA’s revised project plan, which would have contravened certain approved criteria and failed to satisfy the applicable legal requirements, HHS’s continuation of certain outreach activities over other forms was a decision based in HHS’s inherent authority to inform the public and did not breach a specific statutory requirement. See B‑115398.33. For example, HHS continued to maintain HealthCare.gov—through which consumers may identify health insurance coverage options; to operate federally facilitated Exchanges; and, to conduct other outreach efforts.[9] Health Insurance Exchanges,GAO‑18‑565 (Washington, D.C.: July 2018), at 2, 4, 23─24, 32─33; see OIG Report, at 5. As the reduction of certain planned outreach activities was within HHS’s discretion and did not result in a program that was inconsistent with the requirements of applicable law, HHS’s appropriations were available for the associated costs.

Agency communications

HHS engaged in several different methods of communication to disseminate information and the Administration’s policy views on PPACA. These communication methods fall into three categories: changes to HHS Web sites, posts on Twitter, and the production and posting of YouTube videos. At issue is whether HHS’s appropriations were available for these communications.

As a threshold matter, an agency’s appropriations generally are available for communicating with the public about both agency activities and the policy views that underlie those activities, unless another provision of law prohibits the use of appropriations for such expenses. See B-329504; B‑329373; B-319834; B-319075; B‑304715, Apr. 27, 2005; B‑284226.2; B‑194776; B‑178648, Sept. 21, 1973. But see B‑329373 (holding that the Department of Energy’s appropriations were not available to disseminate information related to health care where the agency failed to show a reasonable and logical relationship between the message and the purposes of its appropriations). In the communications at issue here, HHS disseminated information about its activities and its policy views. For example, HHS changed its Web site to state that PPACA has “done damage” and has “created great burdens for many Americans.” Providing Relief Right Now for Patients. HHS also used Twitter to disseminate its views on PPACA and on pending legislation to amend PPACA. In addition, HHS created and disseminated YouTube videos advancing its views on PPACA. All of these communications concerned health care, a subject that is within the purview of HHS. Accordingly, HHS appropriations were available for these communications, unless another provision of law prohibited the use of appropriations for these particular expenses.

There are four statutory prohibitions relevant here. The first two apply governmentwide, with one provision barring the use of appropriations for publicity or propaganda and the other for grassroots lobbying. The third provision prohibits agencies that receive appropriations from the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act from using such appropriations for grassroots lobbying and places limits on the use of such appropriations for grant and contract recipients. Lastly, the fourth prohibition applies to amounts collected pursuant to section 1311 of PPACA and provides that such amounts are not available for the promotion of Federal or State legislative and regulatory modifications. We consider each of these statutory prohibitions in turn.

(1) Publicity or propaganda

Section 718 of the Financial Services and General Government Appropriations Act, 2017, provides: “No part of any appropriation contained in this or any other Act shall be used directly or indirectly, including by private contractor, for publicity or propaganda purposes within the United States not heretofore authorized by Congress.” Pub. L. No. 115-31, div. E, title VII, § 718, 131 Stat. 135, 381 (May 5, 2017). This provision prohibits three forms of communications: those that are purely partisan, self-aggrandizing, or covert. B‑320482, Oct. 19, 2010. We discuss each of these three impermissible forms of communication in turn.

(a) Publicity or propaganda – purely partisan communications

We have found communications to be purely partisan if they have no connection to an agency’s official duties and are completely political in nature. B-319075; B‑147578, Nov. 8, 1962. We balance the bar against purely partisan communications with the agency’s authority to explain and defend its policies. B‑302504, Mar. 10, 2004. To restrict all materials that have some political content or express support for an Administration’s policies would significantly curtail the recognized and legitimate exercise of an agency’s authority to inform the public of its policies, to justify its policies, and to rebut attacks on its policies.

Our case law notes the difficulty in distinguishing between the political and nonpolitical, as the lines separating the two cannot be precisely drawn. B‑147578. Moreover, the role of the President’s cabinet and the agencies that the cabinet members lead necessarily involves advocacy and defense of Administration policies. See, e.g., B-304228, Sept. 30, 2005; B‑147578. We have acknowledged that a determination that an agency’s communication can be characterized as political does not equate to that communication being purely partisan. See B‑319075 (“The [purely partisan] prohibition does not bar materials that have some political content or express a certain point of view on a topic of political importance.”). Rather, the purely partisan restriction prohibits agency communications that are designed to aid a particular party or candidate, or are completely devoid of any connection to official duties. B‑319075; B‑147578.

For example, the Department of Education issued a task order with a public relations firm for a media analysis to assist the Department “in determining if the public [was] gaining an understanding of the [No Child Left Behind Act].” B-304228. As part of the Statement of Work, the Department sought analyses on whether the issue was being mentioned positively in the media. Id. As one of the factors in assessing positivity, the contractor looked for messaging indicating a positive public perception of a particular political party’s commitment to education. Id. While we questioned the effectiveness of assessing positivity as a means to determining public understanding of the law, we did not find the overall analysis improper. Id. The Department asserted that the media analysis was intended to identify where more information on the beneficial qualities of the law was needed, and to ensure that parents had accurate information. Id. However, we found the individual factor focusing on public perception of a particular party’s commitment to education to be purely partisan, as we could not determine any use for the information except for purely partisan purposes. Id.

When HHS created a Web site, HealthReform.gov, dedicated to the previous Administration’s position on health care reform, we did not find the content to be purely partisan. B-319075. The Web site contained reports and articles supporting the Administration’s position, statements by members of both major political parties, and a forum for visitors to state their support. Id. HHS described the Web site as a valuable form of communication in an “e-environment.” Id. Recognizing that the issue of health care reform is “subject to a highly spirited discussion and debate on the national level,” we explained that the purely partisan restriction is a prohibition on communications that are completely political in nature, not a bar on materials that have some political content or express a certain point of view on a topic of political importance. Id., at 8. In B‑302504, we found that HHS’s positive presentation of a new Medicare law as the “Same Medicare. More Benefits[,]” though omitting more comprehensive information on the law such as points of concern held by critics, was not purely partisan communication. B‑302504. While, similar to the Web sites in B‑319075, the advertisements were not free of political tone, the material was not so partisan in nature as to violate the prohibition. Id.

In this case, the changes made to the HHS Web sites, the communications on Twitter, and the videos that HHS produced all bore a connection to HHS’s official duties. The communications concerned health care, a matter that is squarely within the purview of HHS. In addition, the communications were not designed solely to aid a particular political party or candidate. Although the communications at issue clearly expressed a particular viewpoint on health care policy and on PPACA, the purely partisan prohibition is not a bar on materials that express a certain point of view on a topic of political importance. B-319075. See also B‑329504 (finding that the purely partisan prohibition did not bar the agency head from explaining his disagreement with the previous administration’s actions or policies where the agency head sought to amend such actions in connection with his official duties).

Because the communications at issue were connected to HHS’s official activities and were not designed to aid a particular party or candidate, the communications were not purely partisan.

(b) Publicity or propaganda – self-aggrandizement

Self-aggrandizement is publicity of a nature tending to emphasize the importance of the agency or activity in question. B-302504. One of the prohibition’s primary targets is communication with an obvious purpose of puffery. Id. In several instances, we have found that an agency’s communications did not constitute self‑aggrandizement. For example, where the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) used “#CleanWaterRules” in numerous social media messages emphasizing the perceived benefits and importance of the agency’s new rule, we found EPA’s messages to be informational, rather than designed to engender praise for the agency. B-326944, Dec.14, 2015. See also B-319075 (HHS’s creation of the HealthReform.gov Web site and the State Your Support Web page dedicated to advocating the Administration’s position on health care reform during the pendency of PPACA did not constitute self‑aggrandizement, as they were not designed to persuade the public of HHS’s importance); B-302504 (HHS cover letter touting the benefits of a new Medicare law with statements including “[a]s a result of a new law, Medicare is making some of the most significant improvements to the program since its inception” and an accompanying letter advising beneficiaries that “[t]his new law preserves and strengthens the current Medicare program” did not constitute self‑aggrandizement, as HHS did not attribute the enactment of new benefits to HHS).

In this case, HHS updated its Web site to discuss changes to the process of obtaining health coverage. It also made changes to the manner in which HealthCare.gov presented costs and savings information. HHS also produced and disseminated several videos concerning health care and issued multiple tweets on the subject. As in the case in which HHS released a cover letter highlighting the benefits of a new Medicare law, some of these communications discussed actions that the then‑current Administration believed were positive. See B-302504. Other communications expressed disapproval of PPACA, and some urged Congress to pass AHCA. Though these communications may have taken a particular viewpoint, they fall within the agency’s authority to explain to the public its activities and the policies that underlie them. It is not puffery for HHS to explain its position on pending legislation, nor to explain why it believes current policies and processes should be changed. Nor does making determinations regarding the display of information on Healthcare.gov or the resulting display itself emphasize the importance of the agency. Therefore, we conclude that the various communications at issue were not self‑aggrandizement.

(c) Publicity or propaganda - covert propaganda

The critical element of covert propaganda is the agency’s concealment from the target audience of its role in creating the material. B‑305368, Sept. 30, 2005; B‑302710, May 19, 2004 (“[F]indings of propaganda are predicated upon the fact that the target audience could not ascertain the information source.”).

For example, we found that CMS engaged in covert propaganda when the agency created and provided news stations with prepackaged news stories, designed to be included in news broadcasts without alteration. B-302710. CMS’s videos did not, within the story or script, identify the agency as the source. Id. This meant that viewers would not be able to ascertain the agency’s role in the creation of the material. Id. Similarly, in another case, we found that EPA created messaging that failed to disclose the agency’s role to the target audience. B-326944. In that case, EPA developed a social media campaign using a platform called Thunderclap, which enabled the agency to share a message using the social media accounts of supporters, thereby amplifying the agency’s message to the friends and followers of those supporters. Id. While the supporters who allowed Thunderclap to share EPA’s message via their social media accounts were aware of the agency’s role in the creation of the message, the message itself did not identify EPA’s role. Id. Because the friends and followers of the supporters on whose accounts the message was shared would not be able to ascertain the agency’s involvement, we found that EPA’s use of Thunderclap constituted covert propaganda. Id.

In contrast, we found that HHS did not violate the covert propaganda prohibition when it produced and aired television advertisements that featured actor Andy Griffith discussing Medicare under PPACA. B-320482. Each advertisement opened with the words “An Important Message from Medicare” and ended with the HHS seal along with contact information relating to Medicare. Id. Two of the advertisements also ended with the words: “Paid for by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.” Id., at 4. The advertisements clearly identified HHS as the source and, thus, were not covert propaganda. Id.

In this case, the statements posted on HHS.gov and the changes made to Healthcare.gov are on HHS Web sites and are clearly identifiable as agency communications. Likewise, the @HHSGov and @HHSMedia Twitter accounts are agency communication channels that are identifiable by the HHS logo and blue verified badge.[10] Tweets appearing on these accounts could easily be attributed to HHS. HHS’s YouTube videos were published to its YouTube channel, which clearly identifies the agency. Similar to the beginning and ending of the Medicare advertisements in our prior case, B-320482, all of the videos, except those in the “Women Small Biz Owners Burdened by Obamacare” collection, displayed HHS’s logo on the screen. Accordingly, we believe that a reasonable viewer would conclude that HHS is the source of the videos.

Even though the “Women Small Biz Owners Burdened by Obamacare” collection of videos did not contain the HHS logo, HHS’s distribution of these videos is distinguishable from the distribution of the materials in the CMS and EPA opinions discussed above. For example, CMS developed prepackaged news stories to be sent to news stations for incorporation into their broadcasts, as though developed by the news stations themselves, and EPA wrote its Thunderclap message to sound like the statement of a supporter, rather than EPA. In contrast, as seen in Figure 1, HHS published the “Women Small Biz Owners Burdened by Obamacare” collection of videos on its official YouTube channel. Unlike CMS and EPA, who developed content to be distributed by third parties, HHS distributed this collection of videos through its own communication channel. Even though this collection of videos did not contain the HHS logo, we view the publication of the videos on the HHS YouTube channel as adequate attribution for the target audience to discern HHS’s involvement in creating the material.

Figure 1: Screenshot of HHS YouTube Playlist—“Women Small Biz Owners Burdened by Obamacare”

Source: YouTube | GAO B-329199

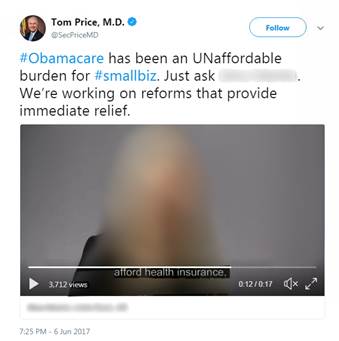

In addition to publishing the “Women Small Biz Owners Burdened by Obamacare” videos on its own YouTube channel, HHS also shared shortened versions of the videos by retweeting some of then‑Secretary Price’s messages. As seen in Figure 2, the videos that then‑Secretary Price had posted on Twitter were embedded, did not link back to the HHS YouTube posting, and did not independently identify HHS. However, the communication created by the agency—the retweet of a post that included the video lacking the HHS logo—was still visibly an HHS message. As a retweet from an official HHS Twitter account, the Twitter message as a whole was sufficient to permit viewers to ascertain the information source. Therefore, we do not find the @HHSGov retweets of these messages to be in violation of the covert propaganda prohibition.

Figure 2: Screenshot of @SecPriceMD Tweet

Source: Twitter | GAO B-329199

We recognize that other social media users could have similarly embedded the “Women Small Business Owners Burdened by Obamacare” videos in their own postings. However, unlike CMS’s prepackaged news stories and EPA’s Thunderclap message, we have no indication that the HHS videos were created for the purpose of distribution through a third party. Rather, any users who shared HHS’s videos acted on their own initiative and not at the behest of HHS. Because the publicity or propaganda prohibition is a restriction on agency communications, the actions of independent third parties do not implicate the prohibition against the use of appropriations for publicity or propaganda.

The changes to the HHS Web sites, the tweets that HHS posted, and the videos that HHS produced and distributed all provide sufficient information to identify HHS as the source of the communications. Therefore, we conclude that none of these communications constitute covert propaganda. Because none of the communications at issue were self‑aggrandizing, purely partisan, or covert, the communications did not violate the prohibition against the use of appropriations for publicity or propaganda.

(2) Grassroots lobbying

Section 715 of the Financial Services and General Government Appropriations Act, 2017, provides:

“No part of any funds appropriated in this or any other Act shall be used by an agency of the executive branch, other than for normal and recognized executive-legislative relationships, for publicity or propaganda purposes, and for the preparation, distribution or use of any kit, pamphlet, booklet, publication, radio, television, or film presentation designed to support or defeat legislation pending before the Congress, except in presentation to the Congress itself.”

Pub. L. No. 115-31, div. E, title VII, § 715, 131 Stat. at 380. We have long construed this language as prohibiting indirect or grassroots lobbying, evidenced by a clear appeal to the public to contact Members of Congress in support of or in opposition to pending legislation. See, e.g., B-326944; B-325248, Sept. 9, 2014; B-270875, July 5, 1996; B-192658, Sept. 1, 1978. A clear appeal must be overt or explicit. B‑329504; B-329373. For example, an agency violated the prohibition on grassroots lobbying when it retweeted a tweet that urged readers to “[t]ell Congress to pass the AIRR Act.” B-329368, Dec. 13, 2017. In contrast, the EPA Administrator did not make a clear appeal where he expressed policy views and encouraged viewers to contact the agency to submit comments in a rulemaking. B-329504. Statements that are simply likely to influence the public to contact Congress also do not constitute impermissible grassroots lobbying if they do not contain a clear appeal. B-304715. We now consider whether three categories of communications constituted impermissible grassroots lobbying: (1) changes to HHS.gov and to Healthcare.gov; (2) the videos HHS produced and disseminated via YouTube; and (3) the Twitter postings.

First, none of the statements on HHS.gov or on Healthcare.gov included a clear appeal to the public to contact a Member of Congress. Therefore, none of the changes to HHS.gov or to Healthcare.gov constituted impermissible grassroots lobbying.

We now turn to the videos. In one of the videos that HHS created, the participant states: “We just need them to repeal, replace, get the job done.” HHS, Women Small Biz Owners Burdened by Obamacare, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xZ8obLaMH4s&list=PLrl7E8KABz1G9hBuZb9nB4VggqAvrfvAC&index=2 (last visited Sept. 24, 2018). In another, a participant expresses his hope that “Republicans . . . can get their act together and deliver relief to the American people.” HHS, Families Burderened by Obamacare, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rV0W6ckqFZ0&list=PLrl7E8KABz1EifD5BWCrauFUNqrMEKAQ0 (last visted Sept. 24, 2018). All of the videos express criticisms of PPACA. These communications expressed a particular viewpoint on legislation. However, violation of the prohibition requires evidence of a clear appeal to the public to contact Congress in support or opposition to pending legislation. B‑304715. The videos contained no such appeal. An expression of a view on pending legislation, without a clear appeal to contact Congress, is not a violation of the prohibition. B‑304715 (noting that executive branch officials may “express[] their views regarding the merits or deficiencies of existing or proposed legislation, even when their objective may be to persuade the public to support the agency’s position—so long as the public is not urged to contact Members of Congress”).

Next, we consider the Twitter postings. Similar to the videos, HHS’s Twitter postings expressed a particular viewpoint on both PPACA and on pending legislation to amend it. In several tweets, then‑Secretary Price discussed AHCA and encouraged Congress to repeal and replace PPACA.[11] However, the grassroots lobbying prohibition does not prohibit an agency from addressing Congress or from publicly stating that Congress should enact particular legislation. Instead, the prohibition bars agencies from making a direct appeal to members of the public asking them to contact members of Congress. B-304715; B‑270875; B‑178648. No such direct appeals to contact members of Congress appeared in the HHS Twitter postings.

However, our analysis of the Twitter postings must also consider the hashtags contained in the postings. HHS used its @HHSGov Twitter account to retweet then‑Secretary Price’s message: “We will continue to work to create a #healthcare system that is truly responsive to the needs of #patients & #smallbiz. #RepealAndReplace.” Because the “RepealAndReplace” moniker was used by others advocating for changes to health care legislation, a user clicking the hashtag could have potentially reached other messages that made appeals to contact members of Congress. For example, one tweet bearing the “#RepealAndReplace” hashtag read: “Call Congress at 202-224-3121 and demand full repeal of ObamaCare #FullRepeal #RepealAndReplace #KeepYourPromise #StandWithRand.”

Even where an agency’s communication, in and of itself, does not constitute a clear appeal, we will find such a clear appeal to exist where a third party makes the actual appeal to the public to contact Members of Congress and the agency endorses or facilitates access to that third party’s message. For example, we found that EPA violated the grassroots lobbying restriction by including in an EPA blog post hyperlinks to external Web pages that contained a direct appeal to members of the public asking them to contact Members of Congress. B‑326944. Specifically, EPA hyperlinked to a Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) Web page, “Brewers for Clean Water,” and a blog post by a self-described environmental action group called Surfrider Foundation. Id. The NRDC Web page included language suggesting the public “take[] action” to help defend clean water, and emphasizing the need for “strong legal protections.” B-326944, at 19–20. Below this text was a prominent link button directing visitors to a form to transmit a message to their senators. Id., at 20. Similarly, the Surfrider Foundation Web page displayed a link button that led visitors to a form to contact Congress to encourage opposition of legislation or amendments in appropriations bills that would undermine the Clean Water Act or EPA’s rule. Id. The text surrounding the Surfrider Foundation link button said “Get Involved” and “Defend the Clean Water Act, Tell Congress to stop interfering with your right to clean water!” Id.

We found that EPA associated itself with the linked content when it chose to include hyperlinks to the Web pages within its official blog post. Id., at 24. This association, combined with the clear appeals contained on the NRDC and Surfrider Foundation Web pages, constituted a violation of the grassroots lobbying prohibition. Id. We explained that the decision to include a hyperlink within the agency’s communication channel was an expressive act that formed a message of the agency’s own, and the fact that the linked content was not EPA’s did not excuse the agency from responsibility for its own message. Id., at 23─24.

In another case, we considered whether the Department of Transportation (DOT) engaged in grassroots lobbying when it retweeted and “liked” a message posted by Steve Forbes, which encouraged readers to “Tell Congress to pass the [21st Century Aviation Innovation, Reform, and Reauthorization Act].” B-329368. The message included a hyperlink to another Web page with a similar appeal and a form to send an auto-generated email to Congress. Id. We found that by retweeting and liking the message, DOT both endorsed the statement and created agency content. Id. As with EPA, DOT associated itself with the Steve Forbes tweet when it chose to share and like the message and was responsible for the DOT message this action conveyed. See id.

In this case, HHS’s retweet contained the “#RepealAndReplace” hashtag. Clicking on this hashtag could have led viewers to other tweets that made direct appeals to contact Members of Congress. At issue here is whether HHS’s inclusion of this hashtag in its retweet constitutes HHS’s adoption of the direct appeals contained in other tweets that used this same hashtag.

While the hashtag function does enable users to follow topics of interest, any user can create a hashtag or include an established hashtag within his message, and there is no requirement as to how the content of the message relates to the hashtag. Accordingly, while it was foreseeable that some Twitter users lobbying for repeal of PPACA or enactment of AHCA would include #RepealAndReplace in their tweets, the hashtag could also appear in tweets discussing another topic entirely.

Tweet authors may also use hashtags so that individuals who are interested in the author’s tweets are more likely to find and read them. See Patrick M. Ellis, 140 Characters or Less: An Experiment in Legal Research, 42 Int’l J. Legal Info. 303, 337 (2014) (“Using hashtags for key words . . . increases the likelihood that [an] account would come up when other users searched [for those hashtags] via Twitter’s query.”). This use of hashtags—that is, to promote visibility of the agency’s message—is within the range of communication activities that an agency may undertake to inform the public of its activities and of the policies that animate them.

HHS’s use of hashtags stands in contrast to the agencies’ actions in our prior decisions where we concluded that an agency adopted a third party’s overt appeal. In those decisions, the agency associated itself with the clear appeal contained in the third-party message by using its own communication channels to endorse or facilitate access to a third party’s materials—in the case of EPA, by choosing to highlight Web pages of environmental action groups within an agency blog post, and in the case of DOT, by reproducing a lobbying message on an official agency Twitter page. In both instances, the agency conveyed a message and the content of the hyperlinked document contributed to that message. In contrast, the nature and purpose of a hashtag prevent us from viewing HHS’s action as an endorsement of every other message that could possibly be reached by clicking “#RepealAndReplace.” It is possible that clicking the “#RepealAndReplace” could have led the reader to ultimately read a message containing a direct appeal to Congress. However, given the vast universe of messages potentially reached via a hashtag, it is also possible the reader would not have read such an appeal and instead would have read one of a multitude of other messages. Because HHS did not facilitate access to a particular third-party communication channel by including the #RepealAndReplace” hashtag, HHS did not adopt any particular message and, thus, did not violate the grassroots lobbying prohibition.

(3) Section 503

Section 503 of the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2017, provides:

“(a) No part of any appropriation contained in this Act or transferred pursuant to section 4002 of Public Law 111‑148 shall be used, other than for normal and recognized executive‑legislative relationships, for publicity or propaganda purposes, for the preparation, distribution, or use of any kit, pamphlet, booklet, publication, electronic communication, radio, television, or video presentation designed to support or defeat the enactment of legislation before the Congress or any State or local legislature or legislative body, except in presentation to the Congress or any State or local legislature itself, or designed to support or defeat any proposed or pending regulation, administrative action, or order issued by the executive branch of any State or local government, except in presentation to the executive branch of any State or local government itself.

(b) No part of any appropriation contained in this Act or transferred pursuant to section 4002 of Public Law 111–148 shall be used to pay the salary or expenses of any grant or contract recipient, or agent acting for such recipient, related to any activity designed to influence the enactment of legislation, appropriations, regulation, administrative action, or Executive order proposed or pending before the Congress or any State government, State legislature or local legislature or legislative body, other than for normal and recognized executive‑legislative relationships or participation by an agency or officer of a State, local or tribal government in policymaking and administrative processes within the executive branch of that government.”

Pub. L. No. 115‑31, div. H, title V, § 503, 131 Stat. at 561. Similar to the governmentwide anti‑lobbying provision, section 503(a) prohibits the affected agencies, including HHS, from participating in grassroots lobbying.[12] Accordingly, before finding a violation of section 503(a), we require evidence that the agency has made a clear appeal to the public to contact Members of Congress in support of or in opposition to pending legislation. B‑319075; B‑270875 (finding that, although subsection (a) of the Labor-HHS prohibition is more detailed than the governmentwide grassroots lobbying prohibition, both provisions “appear to have the same legal effect”). As explained in our discussion of the governmentwide grassroots lobbying prohibition above, HHS did not make a clear appeal to the public in its Web site statements, the videos it produced and disseminated via its YouTube channel, or its Twitter postings. Because HHS did not make a clear appeal, HHS did not violate section 503(a). Accordingly, at issue here is whether HHS violated section 503(b).

Unlike section 503(a), which restricts an agency’s own activities, section 503(b) places limits on a grant or contract recipient’s use of funds derived from appropriations for certain lobbying activities. Pub. L. No. 115‑31, § 503, 131 Stat. at 561. Specifically, it prohibits grantees or contractors from using federal funds for any activity designed to influence the enactment of, among other measures, legislation before Congress. Id. See B‑202787(1), May 1, 1981 (evaluating lobbying activities by a Community Services Administration grant recipient in light of the subsection (b) prohibition). Here, HHS obligated amounts for contractor support for its television studio, HHS.gov, and Healthcare.gov, all of which are operated by HHS employees.[13] As a threshold matter, we must determine whether the phrase “grant or contract recipient” includes a situation where, such as here, a contractor provides support services for an activity that is directed by the agency. As explained below, we conclude that it does not.

As with any question of statutory interpretation, we begin with an analysis of the statute’s text. Jimenez v. Quarterman, 555 U.S. 113, 118 (2009); B‑329603, Apr. 16, 2018. Here, by the plain language of section 503(b), the provision applies to the salaries and expenses of, in relevant part, “contract recipient[s].” See B‑248812.2, May 4, 1993, at 8 (finding that the then‑current version of section 503 placed an independent obligation on grant or contract recipients to avoid the use of federal funds for lobbying). In other words, the provision applies to an organization or individual that is awarded a contract with an agency that, in turn, receives its appropriations from the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, Related Agencies appropriations act. Based on a literal reading of this language, section 503(b) would apply to HHS’s use of its appropriations for the salaries and expenses of its contract recipients: namely, the private contractors who provide HHS with television studio and Web site support services. However, we believe that such an interpretation would contravene the purpose of the exception in section 503(a) that provides for direct contacts with Congress.

In interpreting a statute, “the words of a statute must be read in their context and with a view to their place in the overall statutory scheme.” FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 529 U.S. 120, 133 (2000) (citing Davis v. Michigan Department of Treasury, 489 U.S. 803, 809 (1989)). Where giving effect to the plain meaning of the words in a statute would lead to an absurd result that is clearly unintended and is at variance with the policy of the legislation as a whole, we will follow the purpose of the statute rather than its literal words. B‑287158, Oct. 10, 2002 (citing Auburn Housing Authority v. Martinez, 277 F.3d 138, 144 (2nd Cir. 2002) (“Statutory construction . . . is a holistic endeavor. . . . The preferred meaning of a statutory provision is one that is consonant with the rest of the statute.”)).

Although section 503(a) prohibits certain agencies from using their appropriations for grassroots lobbying, it expressly permits such agencies to use their appropriations to lobby Congress directly. Pub. L. No. 115‑31, div. H, title V, § 503(a), 131 Stat. at 561 (prohibiting lobbying “except in presentation to the Congress . . . itself”). In contrast, section 503(b) applies to an agency’s grant or contract recipients and, unlike section 503(a), does not explicitly authorize private grantees or contractors to lobby Congress directly. Id. § 503(b), 131 Stat. at 561 (permitting only “normal and recognized executive‑legislative relationships”).

Here, HHS stated that the television studio and the HHS Web sites—HHS.gov and HealthCare.gov—are operated by HHS employees with contractor support. Response Letter, at 4, 8. According to the task order for studio support services, the contractor is to provide video production, post‑production, and day‑to‑day audio/visual support and maintenance “as directed” and “depending on the needs of the client.” Task Order, at 8─9. Were section 503(b) to apply to these agency‑directed, contractor‑supported programs, the prohibition would effectively bar HHS from lobbying Congress directly using programs that it controls and operates with the support of private contractors. In other words, section 503(b) would prohibit HHS from partaking in an activity that section 503(a) expressly permits.

As an example of the potential impact of such an interpretation, consider a situation in which an agency both is subject to this prohibition and obtains information technology services from a private contract recipient. In accordance with the terms of the contract, the contractor monitors, fixes, updates, and provides general support for the agency’s electronic communications and telecommunications systems. In contrast to section 503(a), which contains a provision allowing agencies to lobby Congress directly, section 503(b) contains no such provision for private contractors. Therefore, because the agency’s electronic communications and telecommunications systems are maintained by a private contract recipient, the agency would be prohibited from sending e‑mails or making phone calls directly to Members of Congress to support or oppose pending legislation despite the fact that the agency is expressly allowed to do so under the terms of section 503(a).

Such a reading not only results in a contradiction within the statute itself, but also frustrates the executive branch’s responsibility of, and interest in, communicating with Congress on legislative matters. U.S. Const. art. II, § 3 (providing that the President “shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient”); Legislative Activities of Executive Agencies: Hearings Before the House Select Comm. on Lobbying Activities, 81st Cong., pt. 10, at 2 (1950) (highlighting the executive branch’s “requirement to express views to Congress, to make suggestions, to request needed legislation, [and] to draft proposed bills or amendments”). See B‑304715. We will avoid construing anti‑lobbying provisions in such a way that would unnecessarily or excessively constrain agency officials’ communications with Congress. B‑317821, June 30, 2009. Here, where a literal interpretation of section 503(b) would defeat the purpose of the exception that Congress outlined in section 503(a), we decline to accept such a construction of the statute.

As such, we conclude that section 503(b) does not implicate agency-directed, contractor‑supported programs where the agency uses federal funds and contractor support to conduct legitimate communications with the public and with Congress regarding its agency activities and the policy views that underlie those activities. In that regard, we find that section 503(b) does not apply to HHS’s contracts for support of its television studio and Web sites, as these were agency-directed, contractor‑supported activities.

(4) PPACA section 1311

Section 1311 of PPACA prohibits the use of certain funds for, among other activities, lobbying. Specifically, section 1311(d)(5)(B) provides that “an Exchange shall not utilize any funds intended for the administrative and operational expenses of the Exchange for . . . promotion of Federal or State legislative and regulatory modifications.” Pub. L. No. 111-148, title I, subtitle D, part II, § 1311(d)(5)(B), 124 Stat. at 178, classified at 42 U.S.C. § 18031. As explained below, this provision applies to HHS’s use of the user fees it collects through federally facilitated Exchanges. Because HHS obligates the Exchange user fees for expenses of the HealthCare.gov Web site, at issue is whether the changes HHS made to the HealthCare.gov Web site promoted Federal or State legislative or regulatory modifications in violation of the section 1311(d)(5)(B) prohibition.

PPACA required the establishment of an Exchange in each state for the purchase of insurance in the individual and small group markets. Pub. L. No. 111‑148, title I, subtitle D, part II, § 1311(b), 124 Stat. at 173, classified at 42 U.S.C. § 18031; Pub. L. No. 111‑148, title I, subtitle D, part III, § 1321(c), 124 Stat. at 186─87, classified at 42 U.S.C. § 18041. See B‑325630, Sept. 30, 2014. If a state elects to not establish an Exchange, section 1321(c)(1) directs HHS to establish and operate an Exchange within that state. Pub. L. No. 111-148, title I, subtitle D, part III, § 1321(c)(1), 124 Stat. at 186, classified at 42 U.S.C. § 18041. Although federally facilitated and State‑based exchanges are each established by a different sovereign, they are equivalent. King v. Burwell, 576 U.S. ___, 135 S. Ct. 2480, 2489─90 (2015) (explaining that federal and state exchanges “must meet the same requirements, perform the same functions, and serve the same purposes”).

Section 1311(d)(5)(A) permits HHS, as an operator of federally facilitated Exchanges, to charge assessments or user fees to participating health insurance issuers to support the operation of the federally facilitated Exchanges. 42 U.S.C. § 18031(d)(5)(A) (“[T]he State shall ensure that such Exchange is self‑sustaining . . .”); id. § 18041(c)(1); Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; HHS Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters for 2017, 81 Fed. Reg. 12204, 12207─08 (Mar. 8, 2016). See 31 U.S.C. § 9701 (authorizing an agency to establish a charge for services provided). Section 1311(d)(5)(B), which places restrictions on the use of funds intended for administrative and operational expenses of an Exchange, applies to the user fees an Exchange collects pursuant to section 1311(d)(5)(A). See Pub. L. No. 111-148, title I, subtitle D, part II, § 1311(d)(5)(B), 124 Stat. at 178, classified at 42 U.S.C. § 18031(d)(5)(B). Here, HHS used the fees it collected for the purposes of section 1311(d)(5)(A) to pay expenses for the HealthCare.gov Web site. Response Letter, at 8. Accordingly, at issue is whether the changes HHS made to the HealthCare.gov Web site promoted Federal or State legislative or regulatory modifications in violation of section 1311(d)(5)(B).

As noted earlier, section 1311(d)(5)(B) prohibits the “promotion” of the modification of certain measures. In ordinary English, the term “promotion” means the “[e]ncouragement of the progress, growth, or acceptance of something” or “furtherance.” See American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language 1403 (4th ed. 2009). This language is similar to that of the Interior anti‑lobbying provision, which prohibits any activity that “in any way tends to promote” public support for, or opposition to, a legislative proposal. Pub. L. No. 115‑31, div. G, title IV, § 401, 131 Stat. at 493. See B‑329504. The Interior anti‑lobbying provision applies to both explicit and implicit appeals to the public and, as such, covers particularly egregious instances of agency lobbying even where such lobbying falls short of actually soliciting the public to contact Members of Congress. See B‑329504.

In determining whether an agency has violated the Interior anti‑lobbying provision, we evaluate a variety of factors, including agency intent. Id. As such, as with the application of the Interior anti‑lobbying provision, here we must look at the specific facts and circumstances of this case to determine whether HHS, in the changes it made to the HealthCare.gov Web site, improperly obligated the Exchange user fees for the promotion of legislative or regulatory modifications at the Federal or State levels.[14]

As described earlier, HealthCare.gov is a Web site through which individuals and small businesses may obtain information on health insurance coverage options. See Pub. L. No 111-148, title I, subtitle B, § 1103, 124 Stat. at 146, classified at 42 U.S.C. § 18003. HealthCare.gov also serves as the interface for the federal marketplace through which users may select and enroll in health care plans. HHS, What is the Health Insurance Marketplace, available at www.hhs.gov/answers/affordable-care-act/what-is-the-health-insurance-marketplace (last visited Sept. 6, 2018).

Here, the President issued Executive Order 13765 on January 20, 2017, announcing his Administration’s policy “to seek the prompt repeal of [PPACA].” Exec. Order No. 13765. In the executive order, the President further declared that, prior to repeal, “it is imperative for the executive branch to ensure that the law is being efficiently implemented.” Id.

The open enrollment period for the 2017 benefit year extended through January 31, 2017. 45 C.F.R. § 155.410. Sometime between January 25, 2017 and February 1, 2017, HHS changed the titles of the four tabs in the “Get Answers” section of the Web site. On January 25, during open enrollment, the tabs read (1) “Top Questions”; (2) “Apply & Enroll”; (3) “Renew or Change Coverage”; and (4) “Costs & Savings.” HHS, HealthCare.gov: How can we help you?, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20170125173804/https://www.healthcare.gov/get-answers/# (archived by Internet Archive on Jan. 25, 2017). On February 1, the updated tabs read (1) “Top Questions”; (2) “Get 2017 Coverage”; (3) “Tax Help”; and (4) “Update & Manage Coverage.” HHS, HealthCare.gov: How can we help you?, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20170201173735/https://www.healthcare.gov/get-answers/ (archived by Internet Archive on Feb. 1, 2017). In its response, HHS stated that it modifies the content of the HealthCare.gov Web site depending on the status of open enrollment. Response Letter, at 7. HHS also explained that this type of change is consistent with its prior practice and “reflect[s] standard changes that occur due to messaging priorities.” Id.

These changes to the HealthCare.gov Web site did not violate section 1311(d)(5)(B). Most significant is the fact that the updates bear no apparent relation to legislative or regulatory modifications. The updated tab titles themselves do not refer to legislative or regulatory reform, and the other material on the Web page likewise makes no such reference. Even under the broad definition of “promotion” as “[e]ncouragement of the progress, growth, or acceptance of something,” or “furtherance,” we cannot view these changes as promoting such modifications where there is no mention of any legislation or regulation, pending or otherwise, or of the need for reform. The fact that these changes to the Web site may have amended how consumers access different parts of the Web site is not sufficient, by itself, to draw a connection between these standard updates and the topic of health care reform.

Further, although the timing of the updates to the Web site happened to coincide with the President’s issuance of the executive order announcing the Administration’s policy to seek the repeal of PPACA, the evidence does not show that this synchronism was intentional. Consistent with HHS’s explanation that the content of the Web site varies based on the status of open enrollment, the timing of the updates here corresponds with the end of the open enrollment period. HHS made similar changes to the “Get Answers” section of the HealthCare.gov Web site in the 2016[15] and 2018[16] benefit years.

Here, where HHS made routine changes to the HealthCare.gov Web site and the Web site made no reference to modifying any legislation, regulation, or to the need for health care reform in general, we cannot conclude that the use of the Exchange user fees for the updates to the Web site promoted legislative or regulatory modifications at the federal or state levels. Therefore, HHS did not violate section 1311(d)(5)(B).

CONCLUSION

Based upon our review of HHS’s activities, as highlighted in your request, and the relevant legal requirements, we conclude that HHS did not violate appropriations law restrictions, or restrictions on the use of Exchange user fees contained in section 1311 of PPACA. We express no opinion on the merits of the health care legislation at issue or the Administration’s policy. If you have any questions, please contact Julie Matta, Managing Associate General Counsel, at (202) 512-4023, or Omari Norman, Assistant General Counsel for Appropriations Law, at (202) 512-8272.

Sincerely,

Thomas H. Armstrong

General Counsel

List of Requesters

The Honorable Robert P. Casey, Jr.

Ranking Member

Special Committee on Aging

United States Senate

The Honorable Rosa DeLauro

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Honorable Claire McCaskill

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Patty Murray

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Richard Neal

Ranking Member

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

[1] Letter from Senator Ron Wyden, Ranking Member of the Committee on Finance, Senator Patty Murray, Ranking Member of the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, Representative Richard Neal, Ranking Member of the House Committee on Ways and Means, and Representative Frank Pallone, Jr., Ranking Member of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, to Comptroller General (June 13, 2017); Letter from Senator Robert P. Casey, Jr., Ranking Member of the Special Committee on Aging, to Comptroller General (July 21, 2017); Letter from Senator Claire McCaskill, Ranking Member of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, to Comptroller General (July 27, 2017); Letter from Representative Rosa DeLauro, House Committee on Appropriations, Ranking Member of the Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies, to Comptroller General (Aug. 3, 2017) (collectively, Request Letter).

[2] Some state‑based exchanges use their own Web sites for enrollment, while other state‑based exchanges have elected to use HealthCare.gov for enrollment. Health Insurance Exchanges,GAO‑18‑565 (Washington, D.C.: July 2018), at 1, 11.

[3] Both the HealthCare.gov and HHS.gov Web sites are operated by HHS employees with contractor support. Response Letter, at 8.

[4] PPACA established the Exchanges. See GAO-18-565, at 1. Each year the Exchanges offer an open enrollment period during which eligible consumers may enroll in or change their health insurance coverage. Id.

[5] The current HHS Public Affairs Twitter account is @SpoxHHS. Twitter, HHS Public Affairs, available at https://twitter.com/SpoxHHS (last visited Sept. 20, 2018). The @HHSMedia tweets referenced in this opinion can be found on the @SpoxHHS account, as cited.

[6] In its response, HHS stated that it based its review, in part, on the representative tweets identified in your letter to GAO and that it did not review “every tweet posted to, re‑tweeted by, or ‘liked’ by the @HHSGov and HHS Media Twitter accounts.” Response Letter, at 2, n.1. See also id., at 9─10. In our consideration of HHS’s Twitter activity, we also based our review on the tweets identified in your letter.

[7] We do not address HHS’s account adjustment methodology in this opinion.

[8] PPACA also requires the establishment of an Exchange within each state to facilitate the purchase of insurance in the individual and small group markets and, where a state elects to not establish an Exchange, that HHS establish and operate an Exchange within that state. Pub. L. No. 111‑148, title I, subtitle D, part II, § 1311(b), 124 Stat. at 173, classified at 42 U.S.C. § 18031; Pub. L. No. 111‑148, title I, subtitle D, part III, § 1321(c), 124 Stat. at 186─87, classified at 42 U.S.C. § 18041. See B‑325630, Sept. 30, 2014. As with state‑based exchanges, such federally facilitated exchanges are required to conduct outreach and education activities that comply with certain standards. 45 C.F.R. § 155.205(e). Because HHS conducts the outreach at issue in this opinion pursuant to its general authority to communicate with the public about agency programs and activities, we do not address whether HHS’s outreach and education activities comply with the requirements for federally facilitated exchanges. Response Letter, at 8. See 45 C.F.R.§ 155.205(c).

[9] For an examination of 2018 open enrollment outcomes and factors that may have affected those outcomes, HHS’s outreach efforts for 2018, and HHS’s 2018 enrollment goals, see GAO‑18‑565.

[10] The blue verified badge denotes that an account of public interest is authentic. See Twitter, About Verified Accounts, available at https://help.twitter.com/en/managing-your-account/about-twitter-verified-accounts (last visited Aug. 6, 2018).

[11] For example, on May 4, 2017, @SecPriceMD tweeted “I applaud the House passage of #AHCA. This is a victory for the American people & the 1st step toward a patient‑centered #healthcare system.” @SecPriceMD, Twitter (May 4, 2017, 02:24 PM), available at https://twitter.com/SecPriceMD/status/860198509651349504. On July 10, 2017, @SecPriceMD tweeted, in part: “Congress must act now to repair the damage #Obamacare has inflicted and provide relief to the American people.” @SecPriceMD, Twitter (July 10, 2017, 05:13 PM), available at https://twitter.com/SecPriceMD/status/884520868445138944.

[12] While the governmentwide anti‑lobbying provision applies only to grassroots lobbying related to legislation pending before Congress, section 503 more broadly prohibits grassroots lobbying related to measures pending at the state or local government level. Compare Pub. L. No. 115-31, div. E, title VII, § 715, 131 Stat. at 380, with Pub. L. No. 115‑31, div. H, title V, § 503, 131 Stat. at 561. We do not address lobbying at the state or local government level in this opinion.