Physician Workforce: Locations and Types of Graduate Training Were Largely Unchanged, and Federal Efforts May Not Be Sufficient to Meet Needs

Fast Facts

The federal government has reported physician shortages in rural areas; it also projects a deficit of over 20,000 primary care physicians by 2025. Residents in graduate medical education (GME) affect the supply of physicians. Federal GME spending is over $15 billion/year.

We found that, from 2005-15, residents were concentrated in the Northeast and in urban areas. And, while many trained in primary care, primary care residents often subspecialize in other fields. Federal efforts to increase GME in rural areas and primary care were limited. In 2015, we recommended HHS develop a plan for its health care workforce programs—it has yet to do so.

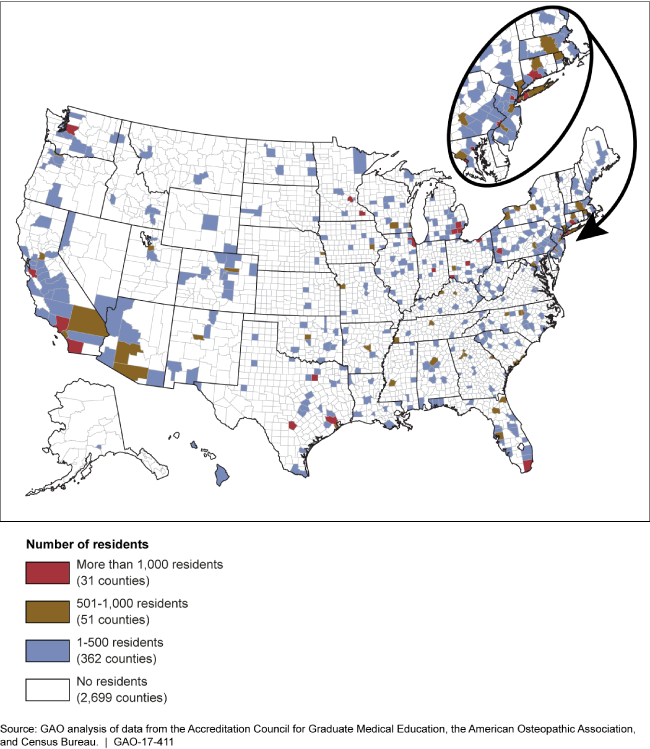

Distribution of Graduate Medical Education Residents in their Primary Training Sites, Academic Year 2015

Map of the United States showing distribution of medical residents.

Highlights

What GAO Found

The locations and types of physicians in graduate medical education (GME) training—known as residents—generally remained unchanged from 2005 through 2015, but there was notable growth in certain areas. As shown in the table below, residents in GME training remained concentrated in the Northeast. At the same time, the number of residents grew more quickly in other regions, though this was somewhat tempered by regional population growth. Residents also remained concentrated in urban areas, which continued to account for 99 percent of residents, despite some growth in rural areas. From 2005 through 2015, over 80 percent of residents were receiving training in a medical specialty, which is required for initial board certification. In 2015, nearly half of these residents were in a primary care specialty (internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics), versus other specialties, such as anesthesiology. While this represented a slight increase from 2010, research has shown that many primary care residents will go on to receive additional GME training in order to subspecialize, rather than practice in primary care. Subspecialty training accounted for less than 20 percent of residents from 2005 through 2015, though the number of residents in subspecialties grew twice as fast as for specialties.

Regional Concentration of Graduate Medical Education (GME) Residents

|

Region |

GME residents, 2015 |

GME resident growth (2005-2015) |

U.S. population growth (2005-2015) |

GME residents per 100,000 population |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2005 |

2015 |

|

Midwest |

31,056 (24%) |

24% |

3% |

38 |

46 |

|

Northeast |

38,951 (31%) |

15% |

3% |

62 |

69 |

|

South |

37,967 (30%) |

28% |

13% |

28 |

31 |

|

West |

19,604(15%) |

26% |

12% |

23 |

26 |

|

National |

127,578 (100%) |

22% |

9% |

35 |

40 |

Source: GAO analysis of data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, the American Osteopathic Association, and Census Bureau. | GAO-17-411

GAO found that the primary federal efforts intended to increase GME training in rural areas were incentives within the Medicare program that can provide hospitals with higher payments for such training. However, hospitals' use of these incentives was often limited, and certain Medicare GME payment requirements could present barriers to greater use.

GAO identified four federal efforts intended to increase primary care GME training. Each effort added new primary care residents and provided funding in areas of the country with disproportionally low numbers of residents or physicians, though to varying degrees. The four efforts accounted for a relatively small percentage of primary care residents and overall federal GME funding, about 3 percent and less than 1 percent, respectively. In addition, the extent to which the residents added by these efforts will be maintained or continue to grow is uncertain, in part because federal funding for some of the efforts has ended. As a result, the efforts may not be sufficient to meet projected primary care workforce needs. Further, GAO recommended in 2015 that the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) develop a comprehensive and coordinated plan for its health care workforce programs, which is critical to identifying any other efforts necessary to meet these needs, and has not yet been implemented.

Why GAO Did This Study

A well-trained physician workforce adequately distributed across the country is essential for providing Americans with access to quality health care services. While studies have reached different conclusions about the nature and extent of physician shortages, the federal government has reported shortages in rural areas and projects a deficit of over 20,000 primary care physicians by 2025. GME training is a key factor affecting the supply and distribution of physicians. Federal funding for this training is significant, more than $15 billion per year, according to the Institute of Medicine. Given the federal investment and concerns about physician supply, GAO was asked to review aspects of GME training.

This report describes (1) changes in number of residents in GME training by location and type of training from academic years 2005 through 2015, (2) federal efforts intended to increase GME training in rural areas, and (3) federal efforts intended to increase GME training in primary care. To determine changes in the locations and types of residents in GME training, GAO analyzed resident data from the accrediting bodies overseeing GME training. To identify and describe relevant federal efforts, GAO also reviewed federal laws, reports, and data, and interviewed agency officials.

Recommendations

GAO continues to believe that action is needed on a 2015 recommendation for HHS to develop a plan to guide its health care workforce programs. HHS provided technical comments on a draft of this report, which GAO incorporated as appropriate.