Human Capital: OPM Needs to Improve the Design, Management, and Oversight of the Federal Classification System

Highlights

What GAO Found

GAO's analysis of subject matter specialists' comments, related literature, and interviews with Office of Personnel Management (OPM) officials identified a number of important characteristics for a modern, effective classification system, which GAO consolidated into eight key attributes (see table below). GAO's analysis shows that in concept the current General Schedule (GS) classification system's design incorporates several key attributes including internal and external equity, transparency, simplicity, and rank in position. However, as OPM implemented the system, the attributes of transparency, internal equity, simplicity, flexibility, and adaptability are reduced. This occurs, in part, because some attributes are at odds with one another so fully achieving one attribute comes at the expense of another. Thus, OPM, working with its stakeholders, is challenged to determine how best to optimize each attribute.

Attributes of a Modern, Effective Classification System

|

Internal equity : All employees with comparable qualifications and responsibilities for their respective occupations are assigned the same grade level. |

|

External equity : All employees with comparable qualifications and responsibilities are assigned grade levels and corresponding pay ranges comparable to the non-federal sector. |

|

Transparency : A comprehensible and predictable system that employees, management, and taxpayers can understand. |

|

Flexibility : The ease and ability to modify the system to meet agency-specific needs and mission requirements, including modifying rates of pay for certain occupations to attract a qualified workforce, within the framework of a uniform government-wide system. |

|

Adaptability : The ease and ability to conduct a periodic, fundamental review of the entire classification system that enables the system to evolve as the workforce and workplace changes. |

|

Simplicity : A system that enables interagency mobility and comparisons, with a rational number of occupations and clear career ladders with meaningful differences in skills and performance, as well as a system that can be cost-effectively maintained and managed. |

|

Rank-in-position : A classification of positions based on mission needs and then hiring individuals with those qualifications. |

|

Rank-in person : A classification of employees based on their unique skills and abilities. |

Source: GAO analysis of subject matter specialists, OPM interviews, and literature reviews.

While the GS system's standardized set of 420 occupations, grouped in 23 occupational familes, and statutorily-defined 15 grade level system incorporates several key attributes, it falls short in implementation. For example, the occupational standard for an information technology specialist clearly describes the routine duties, tasks, and experience required for the position. This kind of information is published for the 420 occupations, so all agencies are using the same, consistent standards when classifying positions—embodying the attributes of transparency and internal equity. However, in implementation, having numerous, narrowly-defined occupational standards inhibits the system's ability to optimize these attributes. Specifically, classifying occupations and developing position descriptions in the GS system requires officials to maintain an understanding of the individual position and the nuances between similar occupations. Without this understanding, the transparency and internal equity of the system may be inhibited, as agency officials may not be classifying positions consistently, comparable employees may not be treated equitably, and the system may seem unpredictable. Several studies have concluded that the GS system was not meeting the needs of the modern federal workforce or supporting agency missions, and some studies suggested reductions in the number of occupational series and grade levels to help simplify the system. In addition, over the years agencies have sought exceptions to the GS system to mitigate some of its limitations either through demonstration projects or congressionally-authorized alternative personnel systems—often featuring a broadband approach that provided fewer, broader occupational groups and grade levels. By using lessons learned and the results from prior studies to examine ways to make the GS system more consistent with the attributes of a modern, effective classification system, OPM could better position itself to help ensure that the system is keeping pace with the government's evolving requirements.

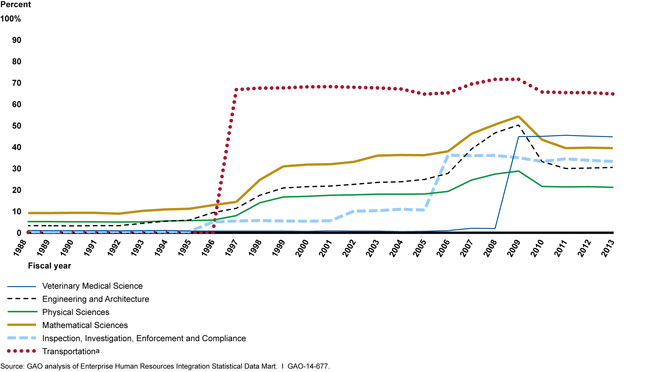

The proportion of federal employees covered under alternative personnel systems increased from 6 percent to 21 percent of the white-collar workforce from 1988 to 2013. Occupational families (i.e., groups of occupations based upon work performed) in the science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields are more prevalent in alternative systems. Of the GS system's 23 occupational families, the 6 with the largest increase from GS to an alternative system were mostly concentrated in STEM occupations (See figure below). GAO estimated that, in 2013, employees in alternative systems were paid about 10 percent more, on average, than GS employees in identical occupations when controlling for factors such as tenure, location, and education in the 90 occupations GAO considered.

Occupational Families with the Greatest Change in Use of Alternative Systems, 1988-2013

aIn 1996, an alternative personnel system was applied to Federal Aviation Administration air traffic controllers at the Department of Transportation. While these occupations are not STEM-related, the alternative personnel system implemented accounts for the increase in 1996.

OPM is responsible for establishing new—and revising existing—occupational standards after consulting with agencies. From 2003 to 2014, OPM established 14 new occupational standards and revised almost 20 percent of the occupational standards. However, there was no published review or update of 124 occupations since 1990. OPM officials said they first review occupations identified in presidential memorandums as needing review; however OPM does not systemically track and prioritize the remaining occupational standards for review. Therefore, OPM has limited assurance that it is updating the highest priority occupations. Further, OPM is required by law to oversee agencies' implementation of the GS system. However, OPM officials said OPM has not reviewed any agency's classification program since the 1980s because OPM leadership at the time concluded the reviews were ineffective and time consuming. As a result, OPM has limited assurance that agencies are correctly classifying positions according to standards.

Why GAO Did This Study

Almost since its inception in 1949, questions have been raised about the ability of the GS system—the federal government's classification system for defining and organizing federal positions—to keep pace with the evolving nature of government work. GAO was asked to review the GS classification system.

This report examined: (1) the attributes of a modern, effective classification system and how the GS system compares with the modern systems' attributes; (2) trends in agencies and occupations covered by the GS system and the pay difference for selected alternative systems; and (3) OPM's administration and oversight of the GS system. GAO analyzed personnel data from 1988 to 2013, conducted a literature review, compared legislation to OPM procedures, and interviewed subject matter specialists and OPM officials, selected to represent public policy groups, government employee unions, and academia, among others.

Recommendations

GAO recommends that the Director of OPM (1) work with stakeholders to examine ways to modernize the classification system, (2) develop a strategy to track and prioritize occupations for review and updates, and (3) develop cost-effective methods to ensure agencies are classifying correctly. OPM partially concurred with the first and third recommendation but did not concur with the second recommendation. OPM stated it already tracks and prioritizes occupations for updates. However, OPM did not provide documentation of its actions. GAO maintains that OPM should implement this action.

Recommendations for Executive Action

| Agency Affected | Recommendation | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Office of Personnel Management |

Priority Rec.

To improve the classification system and to strengthen OPM's management and oversight, the Director of OPM, working through the Chief Human Capital Officer Council, and in conjunction with key stakeholders such as the Office of Management and Budget, unions, and others, should use prior studies and lessons learned from demonstration projects and alternative systems to examine ways to make the GS system's design and implementation more consistent with the attributes of a modern, effective classification system. To the extent warranted, develop a legislative proposal for congressional consideration. |

Although OPM originally partially agreed with this recommendation, it later reported that it concurred with the recommendation. To fully implement our recommendation, OPM needs to follow through on developing, piloting, and implementing various classification modernization efforts. As of March 2025, OPM stated that it is currently conducting a pilot, known as the Skills-Based Hiring for IT Management Positions Project. The purpose of this project is to transition the IT Management job series to fully skills-based hiring by the end of 2025. Separately, OPM also plans to update its Competency-Based Classification and Qualification Policy by June 2025 and later test it prior to final issuance. According to OPM, it is exploring how to use artificial intelligence to inform this policy. Completing these and similar efforts would position OPM to help ensure that the federal classification system is keeping pace with the government's evolving requirements.

|

| Office of Personnel Management | To improve the classification system and to strengthen OPM's management and oversight, the Director of OPM should develop cost-effective mechanisms to oversee agency implementation of the classification system as required by law, and develop a strategy to systematically track and prioritize updates to occupational standards. |

In its 60 Day Letter, OPM stated it did not concur with our recommendation to develop cost-effective mechanisms to oversee agency implementation of the classification system by systematically tracking and prioritizing updates to occupational standards. OPM reported that it currently tracks and prioritizes updates to occupational standards based on the individual and collective needs of the agencies. OPM also reported that in carrying out its responsibilities for developing and issuing classification standards, it is continually involved in conducting occupational studies and writing new standards.

|

| Office of Personnel Management | To improve the classification system and to strengthen OPM's management and oversight, the Director of OPM should develop cost-effective mechanisms to oversee agency implementation of the classification system as required by law, and develop a strategy that will enable OPM to more effectively and routinely monitor agencies' implementation of classification standards. |

In July 2014, we found that OPM could benefit from a more strategic approach to creating and updating occupational standards. We found that several of the occupational standards had not been reviewed or updated in several decades. For example, we found roughly 30 percent of the total GS systems occupations had not been reviewed or updated since 1990. We recommended that OPM develop cost-effective mechanisms to oversee agency implementation of the classification system by developing a strategy that would enable OPM to more effectively and routinely monitor agencies' implementation of classification standards. OPM implemented a new process to streamline their review of occupational studies. This process utilizes a data driven process and literature reviews to conduct classification studies, according to OPM. As a result of implementing this new process, OPM was able to increase the number of occupational studies they could complete--over 60 in the past five fiscal years. This is an increase in the number of occupational studies OPM was able to complete over the years we reviewed during the course of our work. Using a more strategic approach to track and prioritize reviews of occupational standards--that perhaps better reflect evolving occupations--helped OPM better meet agencies' evolving needs and the changing nature of government work. Further, the more strategic approach to oversight could help OPM better fulfill its responsibility to ensure agencies are correctly implementing the classification process.

|